ISIS Recoding Life Project

IAS Fellowship

deCODE Comments

Open Reading Frames

ISIS Publications

Links

Contact us

Search

Projects Overview

MilWaste Program

Amazon Project

Quantum Physics

Seminars

Science Dialogue

Recoding Life

ISIS Fellows

Open Reading Frames: The Genome and the Media - Mike Fortun - Page 5

|

It was at the time billed as the largest deal ever between a genomics company and a major pharmaceutical company - and highly symbolic for Iceland in particular, as evidenced by the public signing ceremony staged for the Icelandic media, in which Prime Minister David Oddson passed the pen between Kari Stefansson and Jonathan Knowles of Roche. In March 1998, legislation was introduced into the Icelandic Parliament - legislation which, thanks to the Icelandic equivalent of the Freedom of Information Act, is now known to have been drafted by Stefansson and deCODE's lawyers rather than the Ministry of Health - legislation that would establish a "Health Sector Database" comprised of the medical records of every Icelander, and grant a 12-year exclusive monopoly license to one anonymous licensee, which everyone knew to be deCODE. That first legislation, which all sides now agree was badly written, was stopped by a number of people in the Icelandic medical and genetics research communities, including Jorunn Eyfjord and Helga Ogmundsdottir at the Icelandic Cancer Research Society, who had done wonderful work on the BRCA2 gene, and Gudmundur Eggertsson, the biologist who had first introduced recombinant DNA techniques into teaching and research at the University of Iceland in the early 1970s. There followed nine months of what is called, for lack of a better word, democratic debate. I went to Iceland for the first time in September 1998 in the midst of this, with daily newspaper, radio and television stories, public talks, and other events happening all around. I'll come back to this in moment. After much public and private wrangling and politicking, the parliament passed the Health Sector Database Act in December 1998, with a 37-20 vote that closely followed party lines (with the conservative Independence Party of Prime Minister Oddson in the majority). The Health Sector Database, which it is important to note has yet to be built, will be combined into what is called the deCODE Combined Data Processing capability (DCDP), that will cross-link the health records with two other databases: a computerized version of the well-maintained genealogical records of Iceland, and a database of newly produced genetic information from blood samples gathered from Icelanders in collaboration with Icelandic physicians (at least some of whom are deCODE shareholders). You may have read all about this in that other New Yorker article about famous genomics company CEOs, "Iceland Decoded" by Michael Specter. (3) A book could be written about the complexities of these events, which is what I'm currently doing. So here I'll just be pulling out a very few strands that illuminate the particularly volatile intersections of genomics and the media that emerged in Iceland, but which may also tell us something about genomics more generally. At every possible opportunity Stefansson and deCODE - the two are even more impossible to separate than Venter and Celera - like to point to the nine months of media frenzy as a sign of the democratic debate which went on in Iceland about the Health Sector Database, conveniently leaving out the fact that he and the company had tried to sidestep any debate at all by trying to rush the first draft of the act through the parliament at the very end of the spring 1998 legislative session.(4) Other anthropologists who have begun to analyze the events in Iceland swirling around deCODE Genetics and the Health Sector Database have written that "some 700 newspaper articles in the press, 150 television programmes, a series of town meetings, and endless discussion and debate both within the Parliament and the shopping centers" can be said to constitute "nine months of national debate" (Pálsson and Rabinow 1999, 14). In a similar vein Paul Billings, a very responsible geneticist by all our usual metrics of responsibility, reassured readers of the American Scientist that "after a broad-based public debate, employing democratic institutions including a free press and independent legislature, the country imposed limits on this new biomedical effort... [T]he construction of science and its associated enterprises by the people of Iceland is paradigmatic; it represents an example of the assertion of national principles and sovereignty over international science and biotechnology. The outcome of gene hunting in Iceland may be better in the end than in North America or Europe" (Billings 1999). |

(3) Michael Specter, "Iceland Decoded", The New Yorker, 18 January 1999, pp. 40-51. The deCODE story is of course much more complicated than I indicate in the main text.

(4) See Stefansson and Gulcher, NEJM.

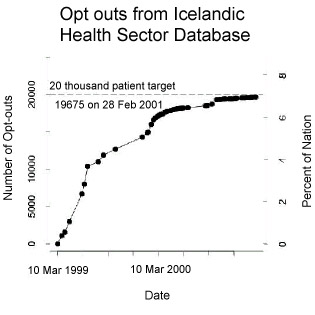

The Health Sector Database of medical records was enacted on the principle of "presumed consent": every Icelander living and dead was presumed to have given their consent to place their medical records in the database, and individuals were then granted the new right to "opt out" of the database - although they could not opt out their dead relatives, even though they share some of the same genetic information. The graph here charts the number of opt-outs, but it also charts some of the social forces in these events. The number of opt-outs rises steeply at first, and then abruptly slows down in June 1999, as most Icelanders mistakenly assumed that this was the cut-off date for opting out. In January 2000, deCODe was formally granted the license to the database, and the opt-out rate increases again as people were reminded of the ongoing reality of the matter. It now appears to be leveling off just as it approaches 20,000 people or 7% of the population, perhaps a reflection of the fact that people are just plain tired of dealing with all of this.

The Health Sector Database of medical records was enacted on the principle of "presumed consent": every Icelander living and dead was presumed to have given their consent to place their medical records in the database, and individuals were then granted the new right to "opt out" of the database - although they could not opt out their dead relatives, even though they share some of the same genetic information. The graph here charts the number of opt-outs, but it also charts some of the social forces in these events. The number of opt-outs rises steeply at first, and then abruptly slows down in June 1999, as most Icelanders mistakenly assumed that this was the cut-off date for opting out. In January 2000, deCODe was formally granted the license to the database, and the opt-out rate increases again as people were reminded of the ongoing reality of the matter. It now appears to be leveling off just as it approaches 20,000 people or 7% of the population, perhaps a reflection of the fact that people are just plain tired of dealing with all of this.